The Lowdown:

November 1, 2011

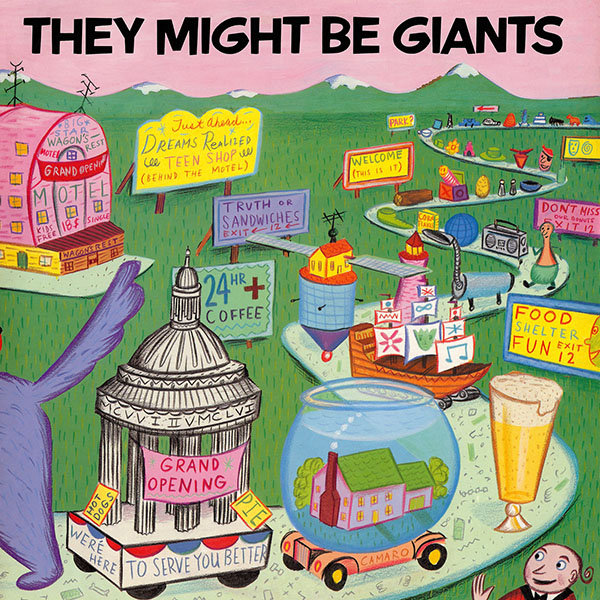

They Might Be Giants: They Might Be Giants

by Jason D. 'Diesel' Hamad

In this modern-day photo (probably taken with something called a digital camera) the founding members of They Might Be Giants display both their original lineup and instrumentation. Left is John Flansburgh, right John Linnell. They may have added more members and the answering machine in their apartment may have been supplanted by podcasts, but the two are still the core of one of rock’s most unique bands. Photo by Shervin Lainez.

Way back in the dark ages—also known as the Reagan Era—a pair of musicians and high school friends both named John (one Flansburgh, the other Linnell) moved into the same Brooklyn apartment building on the same day and promptly formed a band called They Might Be Giants. It would be no exaggeration to say that this was the unofficial genesis of the Brooklyn indie rock scene.

The two were pioneers in many ways. First, their music was like nothing anyone had ever heard. Featuring Flansburgh on guitar and Linnell on accordion and saxophone, it was often backed by a drum machine, presaging electronic music. Their lyrics were… well insane. They were packed with literary goodies and wordplay, often dark, yet absurd to an extreme degree. It was as if Sylvia Plath, Charlie Chaplin and Salvador Dali had decided to collaborate on a music project and gotten Andy Warhol to back them. Their prop-heavy and hilarious live shows helped make Alphabet City and the Lower East Side the center of culture that it is today.

They also pioneered new ways to distribute their tunes. At one point, after Linnell injured his wrist and the band was unable to play live, they decided to start recording their songs into a crappy, often broken answering machine (Remember those things? If you don’t, watch the opening of the Rockford Files), advertising the number in the Village Voice and around town. Dial-a-Song soon became an underground phenomenon, with hundreds of people across the country quietly embezzling company resources to call the (718) number so they could listen to the band’s latest goodies for free (remember when you had to pay for long distance?), a practice the band encouraged with the slogan “Free when you call from work!”

These efforts did not go unnoticed, nor did the band’s hilarious live performances, and on November 4, 1986, they released their debut LP, They Might Be Giants. Nicknamed “The Pink Album” by fans on account of the color’s prominence on the cover, the release was not a huge commercial success, but it established the band as a force to be reckoned with on the college rock scene—a fan base they maintain to this day—getting heavy play on university radio stations. It also featured a number of songs that have become enduring staples, including the MTV hit “Don’t Let’s Start.” Most importantly, it introduced the world to the They Might Be Giants style, which—even through the addition of a full band and other changes—has kept the band going strong and kept fans coming back for three decades. With 19 tracks ranging from just 25 seconds to a bit over three minutes, the album was emblematic of the band’s combination of more traditional-length pieces and mini-songs that were little more than snippets. Sparsely arranged, it was typical of most of their early work, heavy on the synthesizer and with light, poppy tunes. It contained all the elements of the TMBG sound right out of the box. Now celebrating its 25th anniversary, They Might Be Giants is still one of the band’s best releases, one of the 80’s best albums, and truly a vinyl essential.

Dropping the needle on side one, the listener is met with “Everything Right Is Wrong Again,” a super-poppy, fast-paced blaze of glory. The song opens up with what may be a scene of highway carnage, but gets more and more surreal as it goes along:

Everything right is wrong again,

Just like in the long, long trailer.

All the dishes got broken and the car kept driving

And nobody would stop to save her.

Wake me when it's over, touch my face,

Tell me every word has been erased.

Don't you want to know the reason

Why the cupboard's not appealing?

Don't you get the feeling that

Everything that's right is wrong again?

You're a weasel overcome with dinge

Weasel overcome but not before the damage done.

The healing doesn't stop the feeling.

Oddly enough, both right in the middle of the tune and at the end, the band takes great pains to announce:

And now the song is over now,

And now the song is over now,

And now the song is over now,

The song is over now.

It goes through several movements in its short two minutes, typical of many of the band’s songs, and the music is dominated at differing times by a synthesizer beat, big guitar chords, wah wah pedal action, and a frantic keyboard part that sounds mysteriously like a Bach toccata. It makes a great introduction to both the remainder of the album and the band’s career.

For those listeners whose minds weren’t completely blown by the first track, “Put Your Hand Inside the Puppet Head” kicks the whimsical factor up even more. With a staccato synthesizer jumping around in a constant dance, the music is even more energetic than the previous track.

Like many of John Flansburgh’s compositions on this album, it deals with the basic shittiness of working pointless, menial jobs, but in a witty and bizarrely metaphorical way. The opening lines seemed eerily familiar to a rustbelt kid hearing it for the first time:

As your body floats down Third Street

With the burn-smell factory closing up,

Yes, it's sad to say you will romanticize

All the things you've known before.

It was not not not so great.

It was not not not so great.

It’s then that the song takes a turn for the really strange:

And as you take a bath in that beaten path

There's a pounding at the door.

Well, it's a mighty zombie talking of some love and posterity

He says, "The good old days never say goodbye

If you keep this in your mind:

You need some lo-lo-loving arms

You need some lo-lo-loving arms"

And as you fall from grace the only words you say are:

Put your hand inside the puppet head.

Put your hand inside the puppet head.

Put your hand inside…

Put your hand inside…

Put your hand inside the puppet head.

Whether or not the “mighty zombie” is a Jesus reference (as I kinda like to think it is), it’s obvious that the song’s main metaphor is of man, the individual, as merely a puppet and a cog in the societal machine. This is made all the more clear by a spoken word section, which is immediately followed by John’s inevitable rebellion:

Memo to myself: do the dumb things I gotta do.

Touch the puppet head.

Quit my job down at the carwash.

Didn't have to write no one a goodbye note

That said, "The check's in the mail, and

I'll see you in church, and don't you ever change."

If the pu-pu-puppet head

Was only bu-bu-busted in…

I'll see you after school.

The music video (above right)-shot on 16mm film back when Williamsburg, Brooklyn was all abandoned warehouses, there wasn't a million-dollar condo that side of the East River, and a "hipster" was thought to be a character from a Jack Keroac novel-features cardboard cutouts of William Allen White, progressive movement icon, turn-of-the-(last)-century newspaper editor, and original coiner of "What's the Matter With Kansas?" who was a staple of early TMBG shows and videos. As is often the case with They Might Be Giants songs, the poppy music and apparent ridiculousness of the lyrics initially belie the deepness of the work. Upon meditation, it is a terrific nonconformists’ anthem and perhaps the band’s first great song. Despite this, it was never released as a single.

The third track, appropriately titled “Number Three” is a meta-textual farce. Opening up in a mock old-timey style with a bare vocal harmony sung over a strong, steady beat, the music soon transitions to a fast-strummed acoustic guitar punctuated by licks on a deep bari sax. It deals with the blight of writer’s block:

There's only two songs in me and I just wrote the third.

Don't know where I got the inspiration or how I wrote the words.

Spent my whole life just digging up my music's shallow grave

For the two songs in me and the third one I just made.

It’s a purposeful throwaway song, suggesting that musicians looking for filler will stick pretty much anything on an album. Of course, with several dozen releases to their name (not to mention the other 16 tracks on this album) the absurdity of the Johns’ mock worry is quite evident.

The next song, “Don’t Let’s Start” was They Might Be Giants’ first single and has become one of the band’s most endearing favorites, despite failing to chart when it was released. It did, however get heavy television airtime, where the black and white, giant fez-sporting video filmed at the site of the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens introduced geek rock to the MTV generation.

The lyrics have been heavily analyzed by the band's notoriously obsessive fans for a full generation now, and although at its heart it is some kind of a love song (or perhaps a breakup song), no one seems to have come up with a satisfying explanation for most of the more obtuse lines. It’s possible that many may actually just be nonsense written to fit the music, a notion bolstered by John Linnell’s oft-repeated explanation that the song is about “not let’s starting” (figure that one out as a grammatical construction). Among the twists and turns, the song is most noted for some of its dark lines immediately juxtaposed with gibberish, such as:

No one in the world ever gets what they want and that is beautiful.

Everybody dies frustrated and sad and that is beautiful.

They want what they're not and I wish they would stop saying,

“Deputy dog dog a ding dang depadepa

Deputy dog dog a ding dang depadepa.”

D, world destruction

Over and overture

N, do I need

Apostrophe T, need this torture?

After the freneticness of “Don’t Let’s Start,” the Johns toned it down substantially for the next track, “Hide Away Folk Family.” At 3:21 it is the album’s longest track, although this might be due more to its slow tempo than anything else. Marked by effects on both the instrumental and vocal tracks, including some wavy action and a reversed section, it is almost like a lullaby in tone and serves as something of a respite, even in its harsher sections. I’ll be honest, I have no fucking idea what this song is about, but that doesn’t mean it’s devoid of cool lines, such as the quirky pun:

And sadly the cross-eyed bear's been put to sleep behind the stairs

And his shoes are laced with irony.

“32 Footsteps” seems to be about an obsessive-compulsive thrown into a bit of delirium by his girlfriend leaving him:

32 Footsteps leading to the room where the paint doesn't want to dry.

32 Footsteps running down the road where the dirt reaches the sky.

32 feathers in my brand-new Indian headdress.

32 new moons shining in 32 skies.

What's the reason? Why'd she go?

Where's my baby? I don't know.

32 Footsteps, counted them myself, 32 footsteps.

With music dominated by drumbeats, supplemented by an accordion, and punctuated by a harmonica, much of the song is sung in kind of a mock-Elvis style, and at several points one fully expects the words “hunka hunka burnin’ love” to be uttered.

At just 26 seconds in length, “Toddler Hiway” is the first of the band’s true mini-songs, displaying a tendency to throw little snippets of songs onto their albums. This one, notable mostly for the cool chanting in the background, is about a girl chillin’ out at Toys ‘R’ Us. At least I think it is. Who knows? With these guys the bike she’s riding may be a metaphor for Henry Kissinger, the parking lot the Holy Land, and the whole thing is really a parable about shuttle diplomacy and peace in the Middle East. But I’m pretty sure it’s just about a little girl playing.

Speaking of kids, “Rabid Child” is a surreal song dominated by synthesized organ and packed with cb radio references:

Rabid Child stays at home, talks on a cb.

Truckers pass calling out their handles to the kid.

Chess Piece Face and the Big Duluth call her every day.

"Hammer down" and "rabbit ears" are the only words they know.

One thing’s for sure: Linnell was a true child of the seventies.

Kicking the tempo back up with a high-hat beat, “Nothing’s Gonna Change My Clothes” is marked by speedy drum licks, fuzzy bass and guitar notes, a deep “yooooooo-oooooooh-ooooooh-oooooh-ohhhh” background vocal and a screamed conclusion. It’s hard to make heads or tails of the lyrics, but like so many They Might Be Giants songs, the nonsense seems to work perfectly in context:

All the people are so happy now; their heads are caving in.

I'm glad they are a snowman with protective rubber skin.

But every little thing's a domino that falls on different dots<

And crashes into everything that tries to make it stop.

And the mirror, it reflects a tiny dancing skeleton

Surrounded by a fleshy overcoat and swaddled in

A furry hat, elastic mask, a pair of shiny marble dice.

Some people call them snake eyes, but to me they look like mice.

And nothing's smelling like a rose

But I don't care if no one's coming up for air.

I know nothing's gonna change my clothes ever anymore.

To start off the album’s second side, the band returned to something more accessible with “(She Was a) Hotel Detective.” The second single, it has since been followed by two similarly named sequels. Featuring a more typical rock sound, the song is guitar-based with accents from a blaring saxophone. The partially animated video, smacking of retro funk (perhaps wholly based on Flansburgh’s famous geeky thick-rimmed glasses), is nevertheless likely the closest the duo has ever gotten to true traditional coolness. The song is about a nice little lady working as, of all things, a hotel detective, a most anachronistic job even back then:

She's got her ear to the walls

And she's tapping the calls.

If you got a secret, boy,

Forget about it!

'Cause she's a hotel detective.

My little hotel detective.

Yeah, she's a hotel detective.

Why don't you check her out?

The track “She’s an Angel,” despite its characteristically preposterous lyrics, is—in its own twisted way—a very sweet love song:

I met someone at the dog show.

She was holding my left arm

But everyone was acting normal so I tried to look nonchalant.

We both said, "I really love you."

The Shriners loaned us cars.

We raced up and down the sidewalk twenty thousand million times.

In keeping with the Johns’ ultra-literary (and often science-based) style, it even comes complete with a faux Thomas Aquinas reference and an explanation of the impossibility of sound in a vacuum:

When you're following an angel

Does it mean you have to throw your body off a building?

Somewhere they're meeting on a pinhead

Calling you an angel, calling you the nicest things.

I heard they had a space program

When they sing you can't hear; there's no air.

Sometimes I think I kind of like that and

Other times I think I'm already there.

The music itself is even sweet. The first section has Linnell singing over a repeating series of bass beats coinciding with drum kicks, but the following section is highlighted by a terrific slide guitar riff over a bouncy bass line and airy synth. There’s no doubt it stands up as an absolutely great little song and remains one of my all-time TMBG favorites.

With an introduction evocative of a 60’s James Bond theme, “Youth Culture Killed My Dog” tells the story of how man’s best friend was driven to suicide by the declining popularity of Burt Bacharach. A Michael Jackson-like “whoo-hoo” flourish on the conjunction “he’d” and a shouted fadeout ending add a little extra style to the vocals, while the line, “But the hip-hop and the white funk just blew away my puppy's mind,” suggests that Rover quite possibly went out like Kurt Cobain.

To explain the next song, “Boat of Car,” I have to make clear that I do everything backwards. I got into They Might Be Giants way before I developed my Man in Black fetish, so it was years before I realized that the prominent sample featured throughout the song was Johnny Cash singing a variant of the title line from his Carl Perkins-penned classic “Daddy Sang Bass.” This is repeated almost ad nauseum as a synthesizer bounces from note to note in the background. At just a minute and sixteen seconds, there’s not much else to it, except for a strange single verse sung overtop an overamped note stylized to sound like a giant steam horn:

I took that car for a ride.

I was trying to get somewhere

But now I'm following the traces of your fingernails

That run along the windshield on the boat of car.

Aside from the possibilities of a tribute to classic Detroit steel and either a steamy sex or murder scene taking place therein, I had no idea what the hell it was about, but at 16 I thought this song was absolutely brilliant. I still don’t understand it, but I still kinda do.

Featuring a distinctly dissonant tone, “Absolutely Bill’s Mood” is a tribute to life in the loony bin. With a rocky edge, a driving beat, and rising keyed chords, it’s got a bit of cool vibe to it. Bill—whoever he is—seems perfectly happy cracking up, and why shouldn’t he? He’s got all the amenities, and company to boot:

My room is comfortably small

With rubber lining the walls

And there's someone always calling my name.

He calls when I'm alone

And he calls when I'm not home

And he calls when I'm stuck out in the rain.

I'm insane.

I'm insane.

I'm insane.

I'm insane.

In the continued saga of the “character” introduced in “Rabid Child,” “Chess Piece Face” asks the all-important question, “What’s gonna happen to Chess Piece Face?” It gives no answers. It’s not supposed to.

In a typical TMBG twist, “Hope That I Get Old Before I Die” juxtaposes a morbid topic with fabulously upbeat, kooky music, highlighted by a great accordion line and plenty of zingy sound effects and samples. If it were played on a bouzouki and a fiddle it would make a great Irish wake song:

Clear off the kitchen table, darling,

For on the kitchen table I must lie.

I'm just tired, for my wife served the banquet of my life

And I hope that I get old before I die.

Ohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh,

It's a long, long rope they use to hang you soon I hope

And I wonder why this hasn't happened,

Why, why, why?

And I think about the dirt that I'll be wearing for a shirt

And I hope that I get old before I die.

Classic. Beautiful. Awesome. I’m not sure about the punctuation.

Speaking of awesome, “Alienation’s For the Rich” is another terrific Flansburgh composition about the work-a-day doldrums. A little bit country and sung in a deep, throaty growl over a strummed guitar, it tells of a man trying to pay for his kid’s education, figure out a changing world, and muddle through life, self-medicating with cheap beer the whole time:

Well, I ain't feeling happy

About the state of things in my life,

But I'm working to make it better

With a six of Miller High Life.

Just drinking and a-driving,

Making sure my dues get paid

Because alienation's for the rich

And I'm feeling poorer every day,

Hey hey hey.

This song is positively glorious—another one of the band’s best—and I feel like it’s one that even They Might Be Giants’ most ardent fans have long ago forgotten. Well, it deserves another spin, because it truly is a great tune.

“The Day.” Yeah. Well. Um. I give up. My closest approximation to an explanation of the topic of this one is the creation of the perfect song—the combination of the musicianship of Marvin Gaye and the lyrical perfection of Phil Ochs—and the orgasmic joy and utopian perfection that would result therefrom. But really, who the hell knows? Maybe it’s just a tribute to two greats who died too soon. Maybe it’s a really early pro-gay marriage anthem (with an interracial twist). Here are the lyrics; you decide:

The day Marvin Gaye and Phil Ochs got married

The trees all waved their giant arms

And happiness bled from every street corner

And biplanes bombed with fluffy pillows

That’s it. Accompanied only by Linnell on accordion, the verse is repeated twice, first in a light, lyrical tone, then in a harsher, more theatrical harmony. Whatever the intended meaning, it’s really, really cool.

To close off the album, “Rhythm Section Want Ad” is another self-referential bit of glory, this time at a frantic pace. It’s all about They Might Be Giants’ own quirks, their geeky poets’ hearts, their strange two-man lineup, and their odd instrumentation. Like Roger Water’s music mogul asking, “Oh, by the way, which one’s Pink?” or Michael Stanley’s critic inquiring, “Do you write words or lyrics first?” several of the lines seem to come from stupid things said to the band in the early years:

It's been a quarter century, but you still don't wanna mess with the Rhythm Section Want Ad. Photo by Shervin Lainez.

Do you sing like Olive Oyl on purpose?

You guys must be into the Eurythmics.

For every one with dollar signs in his eyes

There must be hundreds who look at you as if you're some kind of

Rhythm section want ad.

No others need apply to the rhythm section want ad

And here's the reason why:

Hats off to the new age hairstyle made of bones.

Hats off to the use of hats as megaphones.

Speak softly, drive a Sherman tank.

Laugh hard; it's a long way to the bank.

The basic meme is let They Might Be Giants be They Might Be Giants, thank you very much. As it turns out, even though they eventually did add that rhythm section, and although they may never have dropped off big rock star paychecks, they’ve been going strong for more than a quarter century and they’ve got a lot left in the tank.

And so that’s it, the album that launched the career of one of the most original bands in rock history. While working on this review, I found myself trying to explain They Might Be Giants to a young barista who was blissfully unaware of their splendor (and yet oh so happy to despoil herself going to a Bon Iver show). I realized there simply is no way to explain They Might Be Giants. Though typically thorough, this article does little to really describe just how awesome they are. If you’ve never heard this album, you’ve just got to listen to it. And if you’ve heard it a million times, listen to it again. It’s worth it every single time.

| mp3 | cd |

|---|---|