The Lowdown:

February 21, 2013

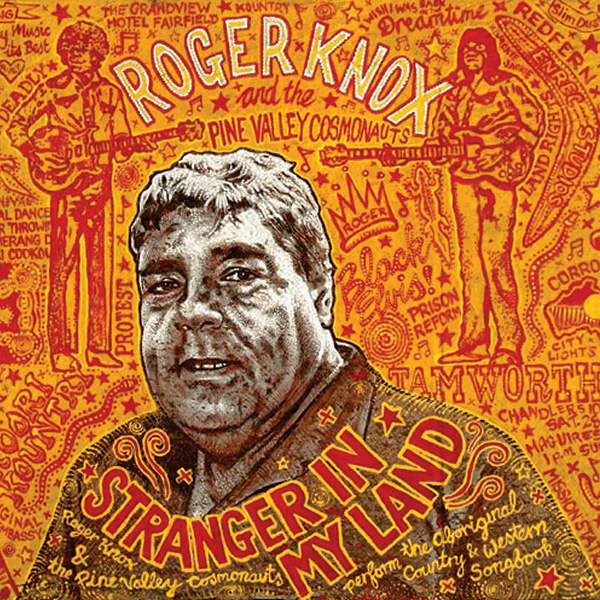

Roger Knox and the Pine Valley Cosmonauts: Stranger in My Land

by Jason D. 'Diesel' Hamad

For untold millennia, music traveled from person to person. This was how it was preserved, stored only in the consciousness of those to whom it brought joy and transmitted organically via a never-ending game of telephone. One person might misremember a word or a note here or there and pass that on to the next generation of listeners. Another might take an old song and change it wittingly, adding his own mark on top of the tradition. Iteration after iteration after iteration the songs changed, morphed, lived, breathed, and sometimes were forgotten and died. This was the norm for almost the entirety of human history. This was folk music. This is where we came from.

The invention of written music changed things. Now it wasn’t necessary to hear a piece of music in order to learn it. Music could be transferred further than the reach of a voice and transmitted across time, exactly as transcribed. Part of the organic process was lost. Different artists might still give songs their own inflection, but a performance of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major today sounds virtually the same as it might have in 1721. The folk tradition still lived, but it now had competition from the forces of musical conformity.

In 1877, Thomas Edison revolutionized the transmission of music once again. With the invention of the phonograph everything changed. Now, the organic process had become completely sterilized. Those first words Edison spoke into his new device, “Mary had a little lamb; its fleece was white as snow…” sound exactly the same today as they did when needle first touched wax. Now, not just music, but actual performances could be passed down to listeners across the world and across generations exactly as they were heard by those present at the creation. Again, the folk tradition survived, but it was pushed further down into the cultural consciousness, replaced by the profit-driven corporate impetus to sell as many records, tapes, cd’s or downloads as possible.

The folk tradition was replaced as the dominant means of transmitting music from one person to another, striking it a devastating blow. Children now didn’t turn to their parents or grandparents to learn the music of their culture, but had it handed to them over the radio waves or accompanied by the ching of a cash register. Music became monetized, began to conform to national and international standards, and many of the regional or cultural traditions that had relied on the folk tradition to keep them alive began to die.

Now, if you’ve followed the circuitous route of this so-called “music review” up to now, stop and reimagine the preceding paragraphs with each instance of the word “music” replaced by “culture.” This is not some theoretical thought experiment; it is exactly what has happened as our world becomes more and more homogenized, as traditions that have lasted for hundreds or thousands of years are subsumed by a cookie-cutter corporate culture that demands conformity in the name of profits. This is how tribal languages are lost and replaced by a broader lingua franca, how culinary traditions are replaced by Starbucks on every corner and how folktales are replaced by the latest Hollywood blockbusters. This is how the entire cultural tradition of humanity dies and is replaced by bland sameness. This is the juggernaut, the great, slow, inexorable genocide that is the story of the modern world. It is the quiet genocide, the forgotten genocide, the one in which lives may or may not be lost, but ways of life certainly are, pulverized beneath the weight of the one true culture.

But there are those who—knowing they could never turn the juggernaut—fought to save whatever they could from beneath its crushing weight. Ironically, in the battle to preserve musical traditions it was recording—the technology that struck many of these traditions a fatal blow—that came to the rescue. A few visionaries like John and Alan Lomax and Moses Asch realized that with the traditions themselves dying, the only way to preserve their artifacts—the songs—for future generations was to record them, and so they dedicated their lives to capturing as much of the world’s fading musical traditions as they could. Even if the traditions themselves were lost forever, their legacy could be maintained for future generations, if only in a dusty museum.

More than just preserving a particular song and a particular performance by a particular person, these archives allow the folk tradition to continue in a modified form. Every time some new listener discovers one of these treasures, they have the ability to incorporate and reinterpret it for themselves, whether they merely sing in the shower or are international recording stars. Every time someone new sings “Goodnight, Irene,” “This Land Is Our Land” or any of the thousands upon thousands of songs that have been thusly preserved, the dream of the Lomaxes and Asches of the world are made manifest. And every time these new singers pass along the music they’ve learned, complete with their own additions and reinterpretations, new life is breathed into the culture that created them in the first place.

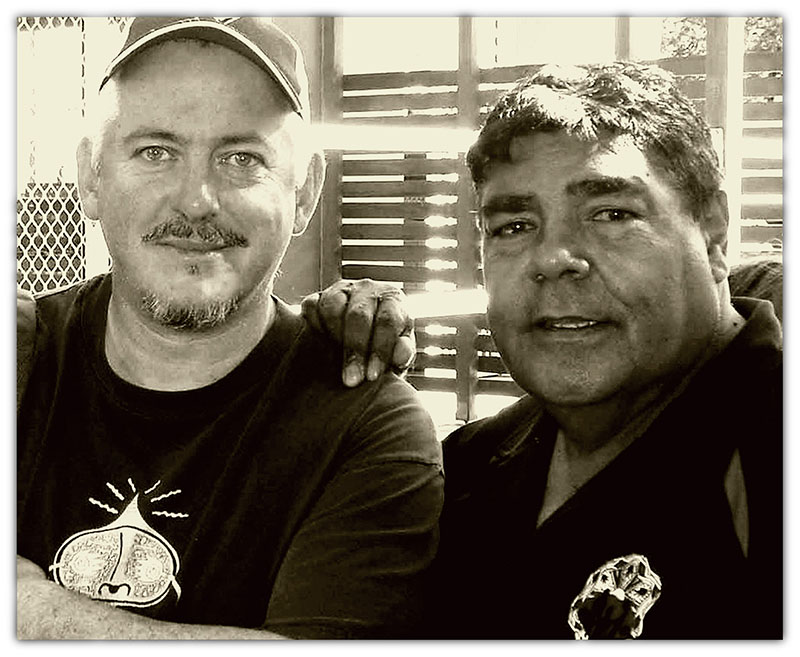

Roger Knox (right)—as much an activist as a native Australian country music legend—corroborated with American Jon Langford (left) and a host of talents spanning two continents to create this powerful collection of aboriginal country and Western music.

A project of this type has recently been completed by Roger Knox, an aboriginal singer known as Australia’s “Black Elvis” but closer in spirit to Billy Bragg or the Man in Black himself, with an activist streak that often leads him to perform in prisons. Accompanied by Jon Langford of the Mekons and Waco Brothers along with a coterie of musical artists from around the world collectively billed as the Pine Valley Cosmonauts—including country great Charlie Louvin in what may be his last recording—Knox has just released Stranger In My Land, an album of covers focusing on country songs written by his native Australian brethren. This group—among the most culturally endangered in the world—adopted the country music that was imported along with American servicemen during the Second World War and made it a vehicle for self-expression, often writing about the alienation they felt as scions of a lost society being forced to assimilate to the culture of their conquerors, thus co-opting a foreign artistic form for their own purposes. Whether overtly political or merely observational, these songs became some of the most powerful means to articulate the story of an all-too-often voiceless people. Many of these singer-songwriters rarely or never recorded, and so their music might be completely lost without such caretakers as Knox, making Stranger In My Land an incredibly important project, perhaps the last chance to preserve these Australian cultural treasures.

Stranger isn’t just an intellectual exercise, though. It is filled with well-executed, catchy songs exhibiting terrific musicianship and centered around the warm, comfy baritone of Knox’s voice. And while many of the stories told in these songs are serious and focus on deep, often saddening concepts, there are bright and comic moments mixed in to balance the listener’s emotions. All of these factors contribute to making this collection an enjoyable experience, even as it fulfils its curatorial and educational missions.

The album starts with a rocking tune called “The Land Where the Crow Flies Backwards,” written by the hard drinkin’ Dougie Young, who sometimes worked as a cowhand when he wasn’t in jail. This outback ranch life is the setting for the song, but by no means its limit. About the same time Mohammed Ali was declaring, “Black is beautiful,” Young was proclaiming his own take on racial identity:

Yes I’m tall, dark and lean, every place I’ve been

The white man calls me Jack.

It’s no crime; I’m not ashamed

I was born with my skin so black.

Likewise, it describes the Western settlement of native lands and even touches on the great atomic power:

Now they laugh in my face;

They say I’m a disgrace;

They say I’ve got no sense.

The white man took this country from me;

He’s been fightin’ for it ever since.

These governments and presidents they arguin’,

Every day they try to start a brawl,

And if there’s going to be a nuclear war

What’s gonna happen to us all?

Knox presents this sharp social commentary in a wrapping of electrified country groove, making it a pill much easier to swallow. The song has a distinct backbeat and is layered with guitars and steel piled upon one another, and occasionally breaking out for a bit of dueling action (with Dave Alvin supplying the blazing wah-wah lines). It’s a damn infectious tune that belies the intricate critiques of its lyrics.

The title song, “Stranger in My Country,” was written by Vic Simms and originally recorded while he was serving time at Bathurst Jail. It confronts the massive alienation felt by members of native groups all around the world who have been turned into second-class citizens in their own conquered homelands:

Well, forgive me if it seems as though, but I am not mistaken,

‘Cos I’m the one that you forgot after my land was taken.

In early years we were put down, cast aside as vermin,

Women men and kids shot down then paid by bible sermon.

Featuring, among others, the Sadies and punk bluesman Andre Williams, the song clips along at pace that makes it hard not to toe tap along.

In contrast to many of the album’s other selections, which mask their commentaries behind country catchiness, “Wayward Dreams” has a powerful, epic feel. The driving bass marches along beneath the layers of strummed strings, chilling violin and operatic backing vocals that set the scene of a Morricone-scored Western faceoff, all as Knox bellows his discontent:

It just so happens that we’re all a part of this land so large and free.

Why can’t people realize how the black man wants to be?

Maybe we can’t walkabout the way we used to do,

But we’d like to be on equal terms and believe in democracy, too.

Yes we are a part of this vast and peaceful place.

Freedom then was a common thing for whole aborigine race.

Why the white man tried to change a way of life, it seems,

Is because it would not fit into their wayward scheming dreams.

Written—again in prison—by Knox’s oft-times concert partner Bobby McLeod, this song, advocating reconciliation and revolution of the mind rather than by the fist, is the best track in the collection.

Another epic, almost operatic selection, “Warrior in Chains” would have been a perfect selection for one of Johnny Cash’s American Albums, with its tale of a man fighting to maintain his humanity in a prison cell. The only song not written by one of Knox’s aboriginal kin, it was instead penned by a brother from another mother, native Canadian folksinger Daniel Beatty, whom Knox met while touring prisons in that country. Struck by the similarities of the indigenous people on both continents, Knox felt it fit right in on this collection. Centered around a prisoner’s sung-out prayer, it is a classic redemption song if there ever was one:

He sang, “Play for me the song of thunder;

Bring to me a dream.

I left my youth behind me

In all the places I have been.

Let your black clouds open over me.

Oh, cleanse me with your rain.

Let your four winds bring some freedom

To the warrior in chains.”

Both more recent and better known than many of the other selections on this album, “Took the Children Away” was a hit for Archie Roach in 1990. Presented by Knox in a rather sweet incarnation with full organ, weeping steel and lovely harmonies by Kelly Hogan, it tells the story of Australia’s program to forcibly remove aboriginal children and place them in boarding schools to assimilate them into the predominant culture. Similar to policies initiated by the American government starting in the late 19th century, Austrialia’s removal programs ended in the late 1960’s, while many “American Indian boarding schools” didn’t close until the late 80’s or early 90’s. Roach himself was placed in one of these schools, as was Knox’s own mother, an emotional burden that seems to come through in his vocals as he sings lines like:

The welfare and the policeman

Said, you’ve got to understand,

We’ll give them what you can’t give,

Teach them how to really live.

Teach them how to live, they said;

Humiliated them instead,

Taught them that and taught them this,

And others taught them prejudice.

You took the children away,

The children away,

Breaking their mother’s heart,

Tearing us all apart,

Took them away.

Written by Denis “Mop” Conlon of Mop and the Drop-Outs, “Brisbane Blacks” examines another problem common to both the Australian and American indigenous population, alcoholism. This song goes far deeper than just blaming economic woes for the common addiction, but digs deeper into the irony of the native Australians’ situation:

With a little help from his friends Roger Knox has crafted an album unlike anything seen before this side of the Pacific, and an album that no country music fan should miss.

Everyday, each passing day, our culture slowly dies,

Like a piece of paper thrown onto a fire.

Now all we’ve got is ancient weapons as our only trade.

Compared to all the immigrants, look how much we made.

You look down through your noses to see

The black man problem down at your feet,

With weary eyes looking up at you

Waiting for the message to get through.

With all the talk these days about the “immigration problem,” this is a poignant reminder that those shouting the shrillest often have the least ground to stand on (at least ground they didn’t steal). Described as a “great big militant sing-along,” that’s exactly what it is, a light-feeling presentation of a heavy subject, all wrapped up in the Sadies’ country rock flair.

Stranger In My Land is a powerful collection full of pointed commentaries on the state of life for Australia’s Aborigines. Its true brilliance, however, is that these commentaries are presented in such an ear-pleasing manner, within songs that would be enjoyable no matter what their topic. And with a Shakespearean understanding for the timing of comic relief, there are moments of frivolity and nostalgia interspersed throughout, making it an even more entertaining experience. There’s no doubt that Roger Knox and the Pine Valley Cosmonauts’ Stranger In My Land is an important album, but it is also just a great listen that no fan of country music—no matter which hemisphere he or she calls home—should miss.

| mp3 | cd | vinyl |

|---|---|---|