The Lowdown:

January 5, 2016

January Featured Review

Daphne Lee Martin: Fall On Your Sword

by Jason D. 'Diesel' Hamad

Daphne Lee Martin at the piano, sword at the ready. You never know when one of those things might come in handy. Photo by Andrew Coutermarsh.

“I wonder sometimes if heaven’s a place where the rivers all flow with gin,” muses Daphne Lee Martin at the opening of her new album Fall On Your Sword, and it’s perhaps the most Daphnesque line ever written. It encapsulates her perfectly: a girl who’s not afraid of a little sin here and there, but who’s sure as hell she’ll make it to heaven if anyone will. Martin is a unique individual, perhaps the fullest embodiment of the artistic ethos I have ever met, someone absolutely determined to do things her own way and to see the world as she sees fit, not as the world itself would have her see it. There is not a single syllable of Daphne’s lyrics, a note of her music, or a moment of her life over which she has not deeply meditated, considered, reconsidered, and framed to fit her overarching vision. Daphne is the wily rabbit she references later on in the album, asking the cruel world not to exile her to the place others fear to tread, because little does it know that’s the only place she’s happy.

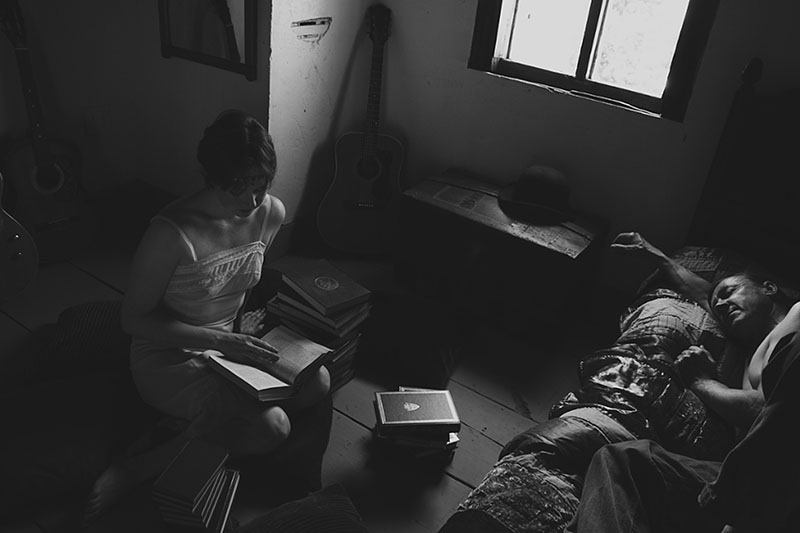

Martin in the guise of a modern-day Scheherazade, ironically enough another storyteller. Photo by Pola Esther.

What’s curious is that this is a uniquely personal opening given that Fall On Your Sword marks something of a departure for the Connecticut songwriter, a venture into lyric storytelling after a pair of thinly veiled poetic memoirs—Moxie with its Dionysian sensuality representing her darker side, while good twin Frost and its sanguine revelry embodies the light. But then, like with any strong-voiced fabulist, Martin’s narratives cannot be divorced from their narrator, and each of the tales—though based on others’ earlier works—is distinctly Daphne-colored in perspective. For literary inspiration, Martin looked to the myths of her formative years—ranging from the bible to the aforementioned Br’er Rabbit—while musically she blends styles spanning from opera to electronica—often within the space of a single song. The result is an incredibly rich tapestry, impeccably conceived and with touchstones across virtually every facet of modern life.

The leadoff track, “Eskimo Bro,” is a modern (and feminine) adaptation of Harry McClintock’s “Big Rock Candy Mountain” (the unsanitized version, before Burl Ives got ahold of it), a somewhat fractured picture of paradise in this world or the next. As Martin says, “if this album is going to be called Fall On Your Sword, I might as well dispense with any veils of innocence right from the word go.” Amid its brassy notes of trumpet, trombone, and sax and gingerly sashaying piano, the gin river line isn’t its only brilliant turn of phrase:

I wonder sometimes if when I die

And the stories are passed around,

Will all of my lovers find one another

As they lower me into the ground?

Lower me into the ground, boys,

Won’t you lower me into the ground?

Lower me into the ground, brave boys,

Won’t you lower me into the ground?

There’s a dream in every penny

At the bottom of the well,

But her teeth in a hot fresh kill

Is how the wildcat measures her wealth.

Daphne can only hope her funeral is so well attended.

As most could probably guess from the title, “Bees Made Honey in the Lion’s Head” dredges biblical myth for its inspiration, specifically the tale of Samson, the hardly-to-be-emulated hero and judge of the Israelites. But rather than dwelling on his lion slaying, it focuses on the betrayal of his most famous lover, and like any good Philistine, Daphne comes down on Delilah’s side of the breakup:

Samson went soft for a woman,

Slept in the joy of his sins;

Woke to cry, “Delilah, why’d you do me wrong?”

“It was the least I could do for my kin.

And if your god would forsake you so easy

—Don’t the proudest go down so hard?—

What good is the strength of a thousand men

If you’ve got no heart?”

One of the album’s most genre-spanning tracks, the song starts out as an organ howling modern funk before throwing in the blues zinger “If I had my way, I would tear this building down,” à la Blind Willie Johnson and the Reverend Gary Davis. Just as the listener thinks he might have a handle on the song, it takes a left turn courtesy SuaveSki, who provides a rap interlude speaking on the part of Samson. Finally, the track breaks down into a Southern gospel hallelujah chorus of “Can’t you hear Jerusalem moan?” (riffed off of the similarly named traditional), interspersed with the temple-tearing line to form a call-and-response chant.

The whole thing is fucking glorious.

Another of the album’s most stellar tracks, “I’d Take a Bullet for You,” examines the underworld exploits of Bonnie & Clyde from the perspective of a love story and against the backdrop of some very Billy Joelesque piano mixed with Arcade Fire:

Wake up. I had the craziest dream.

We hatched the craziest scheme.

And sure enough you’re here asleep beside me.

The perfect drug runs through both of our bloods.

I’m such a sucker for a happy ending.

Wake up and make love to me.

The happy ending, of course, did not materialize for the duo, but represents the best hopes of anyone living their life, which Martin summarizes as, “Go crazy, take what we want, and make love on the run.”

Daphne as Ariadne, Mistress of the Labyrinth, missing some string but looking very defiant & romantic herself. Photo by Pola Esther.

The centerpiece of the track is a reading from a portion of a poem written by Bonnie Parker in 1932, while she was jailed in Kaufman, Texas awaiting trial. The inclusion of the piece speaks not just to Martin’s respect for Parker as a poet, but for her devotion to the romance of the outlaw lifestyle, whatever form it might take.

With its Spanish-inflected guitars and insistent trumpet, perhaps one of the most deeply referential and deeply personal tracks on the album is “Love Is a Rebellious Bird,” a thematic amalgam of the song of the same name from Georges Bizet's 1875 opera Carmen and a number of personal loses suffered by Martin during the run-up to this album’s production in 2014. The eagle and snake featured prominently in the song are references to tattoos belonging to two of the friends who died that year, as well as the legend of Quetzalcoatl as it fits into Martin’s fascination with Central American folklore and what she sees as polytheism’s sense of personal responsibility when compared to monotheism’s reliance on the whims of an opaque deity. The piece is held together by a brilliant vocal performance by Robert Zeigler embodying the fieriest of fire-and-brimstone preachers.

Another example of pure brilliance is the closing track, “A Maturity of Proof,” a biting take on man’s ability to hate wrapped up in birdsongs, pattering rain, and the swaying boardwalk melody of a squeezebox. Based on de Balzac's “The Succubus,” it takes the album full circle from its gin-soaked heaven as it lists all the imaginative ways to dispose of those you don’t like or simply don’t understand. Martin seems to take it very personally:

They used to send girls like me swimming;

The old women sewed all our skirts full of stones.

But if the river proves too shallow, it’s off to the gallows.

Necks are all but meant to break.

Toss a loop of rope round the arm of the oak

in a spectacle of fear and hate.

But if I should climb down from her branches

The cruel world will see it’s the fire for me.

So with a heart as warm as brimstone,

Blue blood and white bone,

Flesh is all but meant to burn.

The rock-infused electric guitar that sneaks in at the end of the track sets the otherwise light-sounding piece in its true context as thunder wells up around it, supplying a hint of disquiet that’s only hinted at in Martin’s ruddy voice.

Having already tackled biblical stories, Martin moves to biblical commentary in “Saint Ambrose Kills His Darlings.” A self-avowed libertine, she takes on the fourth-century ascetic bishop who famously warned his followers to pass over the flames of lust and who was fond of quoting Proverbs 6:28, "Can one walk upon coals of fire and not burn his feet?"

Daphne’s response, delivered in a libidinous deep-throated voice, seems to be, “I don’t know. Let’s find out.”:

Will you make your darlings your doubts

And throw a match on oil

And make this unholy mistake?

Or will you lay everything down

On the one in a million chance

That you have what it takes

To fly through the candle and not burn in the flame?

It strikes me that these lines are as applicable to Martin’s musical exploits as to her carnal escapades, showing her absolute devotion to forging the life she wants to live, no matter the odds against success in others’ eyes.

Built around an extended sample of Robert Beverly Hale reciting the poem “Ode” by Arthur O'Shaughnessy, “Dreamchaser” is a passionate pæan paying homage to the artists, “the movers and shakers / Of the world for ever, it seems.”

“The gift and curse of being an artist is seeing the world as you want it to be rather than how it is,” says Martin, for whom the artistic being is obviously a very personal topic, as evidenced by the fact that the track closes with a recording of her own heart, as if it is only the ability to create that keeps it beating.

Daphne gives her best wistful goodbye glance—as wistful as one can be with that sly little smile that never seems to leave her lips—but don’t let Fall On Your Sword pass you by without giving it a good listen. It makes great music for the beach or wherever you happen to be. Photo by Andrew Coutermarsh.

A mixture of Ecclesiastes and e.e. cummings, “Yet the Sea Is Never Full” is an admonishment to go with the flow, or, as Daphne puts it, “being grateful for what you have… Shit is not always going to go your way and how you choose to embrace what you do get tends to set you up for what you want in the future. Things tend to find their level.”:

But I will take that sun into my mouth

And none but light will issue out.

Call me lawless, far too free;

This river’s always been enough to fill my cup for me.

With a brassy theme that seems to set it on the gritty, rainy city streets of a film noir mystery—mixed as only Martin can with a bit of kitchy 80s synth à la “Axel F” and a voice recording of Warhol Factory “It Girl” Edie Sedgwick—“La Rochefoucald & a Bottle of Boone’s Farm” tells of young love from the perspective of someone who’s seen a lot since those early, heady days. As Daphne puts it, “To be 16 years old and in love for the first time, knowing with that old soul that these feelings would never come again. To be so sure of nothing at all.”

A tale for the underdog, “Laughing Place” examines the difference between justice and legality with references to Prometheus and the original trickster rabbit (long before Bugs).

With its jazzy 5/4 clarinet, “Willing Victim” is about the unveiling of illusions, “my satori song,” as Martin characterizes it:

Lie to me, lie to me, please, just be kind to me.

I know I’ll get no sympathy here.

In short, it’s hard to find a more fascinating album than Fall On Your Sword or a more brilliant songwriter than Daphne Lee Martin. The level of detailed thought put into each and every word, every note, every nuance is simply astonishing. With touchstones in such a broad range of musical genres, this album is sure to have entry points for any listener, and for those who—like me—relish the crossroads of styles, it reads like a map of Clarksdale, Mississippi. Fall On Your Sword is a captivating work of pure art that is not to be missed.

| mp3 | cd |

|---|---|

Follow @NoSurfMusic