The Lowdown:

October 1, 2011

Peter, Paul and Mary: Moving

by Jason D. 'Diesel' Hamad

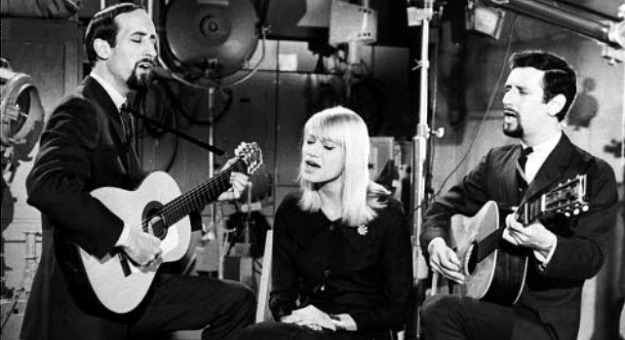

Peter, Paul and Mary, back in the day. (l-r) Peter Yarrow, Mary Travers, Noel Paul Stookey. Despite the band's prodigious talents, don't think for a second those legs didn't sell some albums, too.

In honor of Peter Yarrow’s recent appearance at the Kent State Folk Festival, this month’s No Surf Vinyl Essentials takes a look at what may well have been Peter, Paul and Mary’s best album, 1963’s Moving.

“Wait,” you say (because you are so eminently knowledgeable about folk music, of course), “Moving has ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ on it. Everyone knows ‘Puff the Magic Dragon.’ It was a #1 single. Ok, on the “Easy Listening” charts, but still… The album itself reached #2 on the pop charts. I thought you were focusing on more obscure, lost gems in this segment.”

Well, sage reader, you are correct. “Puff the Magic Dragon” was a huge hit and it continues to be the group’s most recognizable song. And this album, the group’s second release, was huge in its day. But can you name any other songs off of the track list? No, I didn’t think so. And there’s a ton of great ones on here. In fact, it’s probably the band’s most consistently great album, despite being overshadowed by In the Wind, which came out later that same year.

One more thing that makes this album particularly special, at least where I am concerned is that it’s the reason I got into folk music to begin with. My mother’s old mono vinyl copy (the same one I’m using to complete this review) was one of the first albums I ever owned, and before I got into Simon & Garfunkel in high school, before I got into Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie in college, before I got into Leadbelly and Pete Seeger, Cisco Huston and the Weavers after moving to New York, Peter Paul and Mary served as an introduction to the entire genre.

In that respect, this band is actually perfect. They’re like the soft-drug version of folk, before you get into the really hard stuff. Based directly and purposefully on 1950’s folk supergroup The Weavers (with one power-voiced woman flanked by several instrumentally gifted men (who could also sing a lick)), Peter, Paul and Mary updated that band’s “citified” sound. That is, while they had a deep background in authentic folk, they didn’t try to reproduce it the way artists with real roots in the varying traditions did. They cleaned them up, gave them a softer, more poppy edge, and in some cases even modified the lyrics to appeal to a more urban audience. There are certainly good and bad aspects to this, but what’s undeniable is that the compositions designed by the three members, Peter Yarrow, Mary Travers and Noel Paul Stookey (yes, he used his middle name because Peter, Noel and Mary just didn’t have the right ring), were highly appealing and gave many terrific traditional songs a new audience they might not otherwise have reached. And for many who were so intrigued by these songs, like myself, it opened the door for the exploration of a whole new type of music.

So let’s explore Moving and see just what makes it such a classic.

Putting the needle down, one is immediately struck by the energetic acoustic guitar work of both Yarrow and Stuckey, the glue that held all the band’s songs together. The upbeat music of “Settle Down” seems like it’s from the sunny early 60’s, but the lyrics have a hint of 30’s tramp to them, a Guthriesque working wanderer feel:

I worked my way from Boston to that San Francisco bay

Baby what I was looking for, I couldn't find along the way.

Why don't you help me brother, I'm a stranger in your town

Why don't you help me sister, and then maybe I'll settle down.

Why don't you help me brother, I‚m a stranger in your town

Why don't you help me sister, and then maybe I'll settle down.

Never been contented no matter where I roam

It ain't no fun to see a settin’ sun when you're far away from home.

Why don't you help me brother, I'm a stranger in your town

Why don't you help me sister, and then maybe I'll settle down.

Why don't you help me brother, I'm a stranger in your town

Why don't you help me sister, and then maybe I'll settle down.

I've worked in the mills of Pittsburgh, in the hills of Tennessee,

Baby all I want is to find a job that will set my mind at ease.

At the same time, it is maybe just as indicative of the feeling of the early 60’s, when the last of the beatniks and the first of the hippies were beginning to search for a new way. That’s why it’s not actually all that surprising to find out that it was actually a fairly contemporary composition, written by Mike Settle, a one-time member of the New Christy Minstrels who would later go on to join Kenny Rodgers & the New Edition.

The buoyant Peter, Paul and Mary version, the shortest song on the album at just one minute and forty-five seconds, sees each of the trio taking the verses in round, while they all join in to form the classic three-part harmonies the group was famous for on the choruses, with Yarrow breaking off from the other two and striking out on his own to echo the others in the last iteration. The music is fueled by one guitar on a fast-strummed rhythm, punctuated by the other punching out hard-plucked, twangy melody. It makes for a terrifically powerful introduction to the album and a prescient theme for the coming decade that would be so influenced by the work of these three musicians.

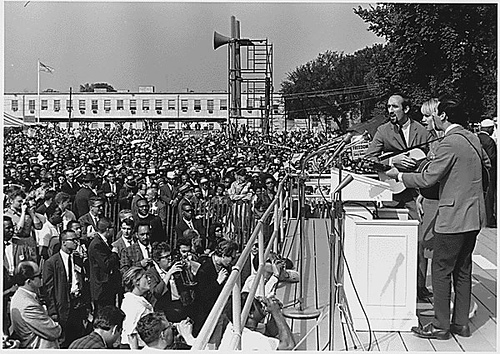

When Peter, Paul and Mary performed at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963 they were already stars, but their participation helped solidify their cache at the forefront of the folk protest movement. Their rendition of fellow perfomer Bob Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind" and their inclusion of the song on their next album helped launch the then-little-known songwriter's career.

The next song, “Gone the Rainbow,” is also prescient, foreshadowing the coming quagmire of Vietnam. The pain of war was a career-spanning theme, starting off with their 1962 debut which featured both “Cruel War” and their classic rendition of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” Of course, at this time the singers couldn’t have known that this was coming and their political attention was turned towards the then-hot civil rights movement, but with hindsight, the song, which features on a lover’s lament at her man being sent off to war and the hardship that this causes, was only a little ahead of itself in terms of zeitgeist. Perhaps better known in the States as “Johnny’s Gone For a Soldier” and sometimes as “Buttermilk Hill,” the song actually originated in Ireland as “Shule Aroon.” Although the earliest printed version of the lyrics seem to date from the late 1800’s, it’s probable the song goes back far beyond that, to the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

With a much more somber tone than the previous track, the Peter, Paul and Mary version features a pair of beautifully plucked guitars, whose notes intertwine as perfectly as the voices of the singers. The group kept part of the Gaelic lyrics as the chorus, although not knowing Gaelic they apparently butchered them into nonsense. The verses are sung appropriately by Mary Travers, whose gorgeous voice does an admirable job of capturing the pure emotion expressed by the female narrator of the song. Quiet and entrancing, it is certainly a song that deserves to be heard, as it amply describes the sad state of those left alone by war.

The next song is one of my favorites, a powerful traditional murder ballad known as “Flora.” Known more popularly as “The Lily of the West,” the origins of this song also come from Ireland, although the Americanized version seems to have originated in England, possibly written by a repatriated American immigrant describing his experiences in the New World. It became extremely popular here in the States, however, and has lived on through many recorded versions. In the original, the girl in the question was named Mary, although it appears some literate rewriter thought the parallel between “Flora” and “Lily” to be too sumptuous to pass up.

The song is told from the lovelorn criminal’s mouth and describes how he met a girl in Louisville who was of such beauty that she was known as the Lily of the West. The two “courted” (how quaint), and although the man hears stories that she’s stepping out on him, he can’t believe it. He sets out to find the truth, and he does, finding her with “a man of low degree” (again, how beautifully quaint), kissing beneath a tree. Well, the rest of the story goes as expected:

I stepped up to my rival, my dagger in my hand.

I seized him by the collar and I ordered him to stand.

All in my desperation I stabbed him in his breast.

I'd killed a man for Flora, the lily of the West.

And then I had to stand my trial; I had to make my plea.

They placed me in a pris'ner's dock and then commenced on me.

Although she swore my life away, deprived me of my rest.

Still I love my faithless flora, the lily of the West.

Although in this version things end very badly for the anti-hero, in others he escapes back across the Atlantic to ramble through Ireland and Scotland.

The Peter, Paul and Mary version is marked, as is often the case, by the trio’s harmonies, which bow and bend in resonance with the emotional tone of each verse. The guitar over which they sing is powerful and quickly strummed as it softens and thunders back to life to highlight the singers’ timbre. All together, it is a terrific, powerful rendition of this awesome traditional.

Calming things down again, “Pretty Mary” is a traditional lament over lost love, this coming in the form of disapproving parents. It’s the old story, “you’re not good enough to marry my daughter.” While in a rock song the boy would fight back and win the girl, shooting off into the night in a puff of exhaust and squealing wheels, but in a folk song, the boy simply leaves, dejected. Told with metaphor and a light hand, the vocals are low-key and sad, as befitting the subject.

Next comes the song that everybody remembers from childhood, “Puff, the Magic Dragon,” listed on the record’s liner notes simply as “Puff.” I’ll not belabor this song since everybody knows it, but I will take a moment to say yes, it really is a children’s song. Rumors that it’s about pot simply aren’t true. It was written in 1959, long before Peter Yarrow was into the stuff, so it simply doesn’t make sense. Ok, I’ll admit, the dragon’s name is “Puff,” the boy is “Jackie Paper,” he “frolicked in the autumn mist” and when Jackie moves on “green scales fell like rain.” It certainly sounds like a lot of marijuana metaphors, but it’s really a song about leaving behind childhood fantasies and taking on the responsibilities of adulthood. It’s not about leaving behind adolescent marijuana habits and moving onto the responsibilities of adulthood (and cocaine). That’s Yarrow’s story and I’m sticking to it.

Peter, Paul and Mary got their start in the Greenwich Village folk club and coffeeshop scene. Their first performance at The Bitter End was in 1961. A year later they were famous all over the world. Shit like that never happens to me.

After that little trip to dreamland, (aka Honahlee), the trio comes back to Earth, closing the album off with a rousing rendition of one of the greatest songs ever penned, Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.” It is done in the Weaver’s style, big voiced and with the radical verses stripped, leaving only the patriotic-sounding shell more acceptable to a wide audience. Still, it is a terrific version of what it is. A ringing acoustic guitar leads the instrumentation with a stand-up bass providing a footing. Although the three part harmonies at the end of the verses and on the choruses are powerful, the star here is undoubtedly Mary Travers, whose powerful voice rivals even the great Ronnie Gilbert, belting out Guthrie’s powerful tribute to his homeland loud enough to hear from sea to shining sea. This was the first version of any Woody Guthrie song that I ever remember hearing, and while it’s polished finish is a far cry from the down-home charm of Guthrie himself, anyone who loves this song should be familiar with this heartfelt and powerful rendition.

Flipping the record over to its second side, the listener is met with another terrifically powerful song, this one a spiritual, “Man Come Into Egypt.” Co-written by Weavers member Fred Hellerman and his frequent collaborator Fran Minkoff, it is a lyrical version of the story of Moses and his quest to free his people from the grip of Pharaoh. Told from the perspective of the common man looking up to his leadership, however, it could apply to many freedom fighters throughout the ages:

There is a man come into Egypt.

He's come for you and me.

On his lips a word is singing,

And the word is liberty.

And the word is liberty, oh, Lord.

And the word is liberty.

On his lips a word is singing,

And the word is liberty.

There is a man come into Egypt

To stir the souls of men

We will follow him to freedom,

Never wear those chains again

Never wear those chains again, oh, Lord,

Never wear those chains again.

We will follow him to freedom,

Never wear those chains again.

With the main part sung by Stookey, this is a hard-hitting song, with the highlights provided by the harmonies of his companions. Especially notable are Travers contributions, which as only stand head-and-shoulders above her companions in terms of sheer power. My only complaint about this song is that Peter, Paul and Mary weren’t patterned quite enough on the Weavers. There’s no Lee Hayes to belt out the bass part that would complete the harmonies. That’s ok, though. Even after two decades of listening to this album, I can’t hear this song without adding it in myself. Try it. It’s fun.

The next song, “Old Coat,” again tones things down, continuing in some ways the religious theme, but at the same time takes a hard look at inequality through the eyes of a young, poor man trying to find his way in the world:

Silver spoons to some mouths, golden spoons to others,

Dare a man to change the given order?

Though they smile and tell us all of us are brothers,

Never was it true this side of Jordan.

Take off your old coat and roll up your sleeves,

Life is a hard road to travel, I believe.

With a simple plucked guitar on melody and another often ghosting it in a higher range, this is one that is particularly dependent on the blending of the three voices, which sing beautifully as one on each chorus.

This slow, sad number is immediately followed by another, “Tiny Sparrow,” a traditional also known as "Come All You Fair and Tender Ladies" or "Little Sparrow." It is an Appalachian ballad, perhaps best known in the version recorded by The Carter Family. Peter, Paul, and Mary, however, forsake the barebones, nasally sung approach of the Appalachian singers, however, creating a rich, beautiful lover’s lament. Mary Travers is the star here, her deep, resonant voice soft yet indescribably rich as it weeps its way through the scorned woman’s tale, while her gentleman companions frame her words with perfect tone that highlights her lead without overshadowing it.

Although the lyrics to this particular version of the song seem to be Stookey et al originals, the song “Big Boat” is derived from an old Tennessee River song called “Alabama Bound,” which focuses more on river life and sinking ships than the lovers’ tale in this version. Quick and lively, this song stands in sharp contrast to its predecessor, proving again that the group’s ability to change gears helped to make this album so great. With the flying guitars and Stookey’s fiery vocal delivery, this song is among the liveliest on the album, helped along by comically Dylanish background vocals by Yarrow and a few key flourishes by Travers.

“Morning Train,” a glorious, haunting spiritual spearheaded by Peter Yarrow, is the album’s penultimate track. It’s credited to Elaina Mezzetti, who also shared writing credit on a number of the other songs on this album (even though most are traditional, the band picked up on the Weavers’ trick of making “substantial changes” (you know, needlessly changing traditional lyrics) so that they could claim writers credits where there were none or effectively steal them from the original authors if the copyright was still extant)). The only problem is that Mezzetti never wrote a word of this song or any other. She was Peter Yarrow’s sister, and he wrote her name in instead of his to provide her with an income. Nice brother, slick trick. Still, despite these technical publishing foibles, this is a great song.

Yarrow’s voice is as powerful as it ever was, crying out like a train whistle in the night while Stookey deftly plucked his guitar underneath. Although Yarrow’s vocals are preeminent, the harmonies, as always, are spot on, and Mary Travers’ are especially soulful, while Paul Stookey’s are especially powerful and full of emotion. The song is the tale of a dying man, grasping a hold of his religion in his last hours:

I'm goin’ home on the morning train.

I'm goin’ home on the morning train.

I'm goin’ home on the morning train.

If you don't see me you can hear me singing.

All my sins been taken away, taken away.

Sister Mary wore three links of chain.

Sister Mary wore three links of chain.

Sister Mary wore three links of chain.

On each link was my Jesus name.

All my sins been taken away, taken away.

I'm on my way to the freedom land.

I'm on my way to the freedom land.

I'm on my way to the freedom land.

Lord God, almighty hold my hand.

All my sins been taken away, taken away.

A little over halfway through the song, the tempo suddenly kicks into high gear and the song transitions into a potent version of “Glory Plow,” the three-part harmonies on the chorus particularly glorious. After this brief zinger, the song seamlessly slips into an up-tempo repetition of the earlier lyrics, ending in a powerful climax.

The final song, “A’ Soalin’” is absolutely a lost classic, based on the English traditional “Hey, Ho, Nobody Home” with additional elements blended by Paul Stookey. It is based on the English tradition of soaling, where the poor would travel from door to door on All Souls’ Day, begging for soul cakes (a flat cake with a cross carved onto it) and other foodstuffs, in exchange for which they would promise to pray for the members of the household and their departed family. Ah, life was so much better before the social safety net, wasn’t it?

Soul, a soul, a soul cake, please good missus a soul cake.

An apple, a pear, a plum, a cherry,

Any good thing to make us all merry.

One for Peter, two for Paul, three for Him who made us all.

The streets are very dirty, my shoes are very thin.

I have a little pocket to put a penny in.

If you haven't got a penny, a hay penny will do.

If you haven't got a hay penny then God bless you.

What makes this song so great is the particular delicacy of the arrangement. Its instrumentation is marked by a low-register guitar providing bass while a finely plucked second dances several octaves above. The vocal harmonies are particularly complex, with the voices often moving in perfect synchronization, and just as often at cross-purposes. All three voices are particularly sweet, and their pleas for scraps to live by seem particularly authentic. Simply put, it is the talents of Peter Yarrow, Paul Stookey and Mary Travers at the absolute height, and it is a purely beautiful song unmatched in their extensive catalogue.

Peter, Paul and Mary was comprised of three very talented musicians, but perhaps their greatest accomplishment was introducing so many great songs to listeners who might otherwise never have heard them and getting millions of people interested in folk music, including your humble author.

As a musical purist, I have significant issues with many elements of the folk revival of the 1960’s, in which Peter, Paul and Mary were instrumental, especially the aforementioned “citifying” (read: watering down) of lyrics and the tendency to blithely take credit for others work, both of which can be traced directly back to the Weavers. But still, there’s no doubt that Peter, Paul and Mary were incredibly talented musicians, singers, arrangers, and even music preservationists, introducing many of these songs to a whole new generation of listeners, and continuing to do so half a century later. While later albums would be marked by the addition of more contemporary writers, such as Bob Dylan, Gordon Lightfoot and John Denver, on this album they were still clearly focused on traditionals. From the standpoint of song selection and the overall quality of their work, this album ranks as their best, and it is absolutely essential for any folk music fan.

| mp3 | cd |

|---|---|