The Lowdown:

July 5, 2011

Bob Dylan: Bob Dylan

by Jason D. 'Diesel' Hamad

Bob Dylan is one of the most well-known and well-respected musical artists in history, especially when it comes to crafting the words that go along with the tunes. Ask a hundred random people who the greatest lyricist of all time is and it’s a fair bet a clear majority will say Dylan. It’s like something pounded into our collective consciousness in grade school through constant repetition: “Bob Dylan is the greatest lyricist who ever lived. Bob Dylan is the greatest lyricist who ever lived. Bob Dylan is the greatest lyricist who ever lived. Bob Dylan is the greatest lyricist who ever lived.” Whether it’s true or not is beside the point (I personally feel that Dylan’s own mentor Woody Guthrie was better, and that Townes Van Zandt, Kris Kristofferson, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Marley, Lucinda Williams and Leonard Cohen all at least give him a run for his money), but how could such a legendary artist have an album that qualifies as a forgotten classic?

Ask those same hundred people which album was Dylan’s first and maybe five will answer correctly. Twenty-five won’t even be able to name a Dylan song; they’ll just remember the rote line that he’s the greatest. Another thirty or so will know “Blonde on Blonde,” “Blood on the Tracks,” and a few others but won’t be able to come close to a useful list. Nearly all the rest will smile confidently and say The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Only the real folk nuts will be able to tell you that his debut was actually a self-titled album released way back in 1962, a full year before Freewheelin’.

In many ways, Bob Dylan was Bob Dylan before there was a Bob Dylan. Oh, sure, he’d already moved from Minnesota, rambled around the country and landed in Greenwich Village. He’d already changed his name from Robert Zimmerman to the much more goyim moniker by which we know him today (rechristening himself after Irish poet (and raging alcoholic) Dylan Thomas). He’d already mastered the guitar and the harmonica and accepted the fact that his voice would never win awards.

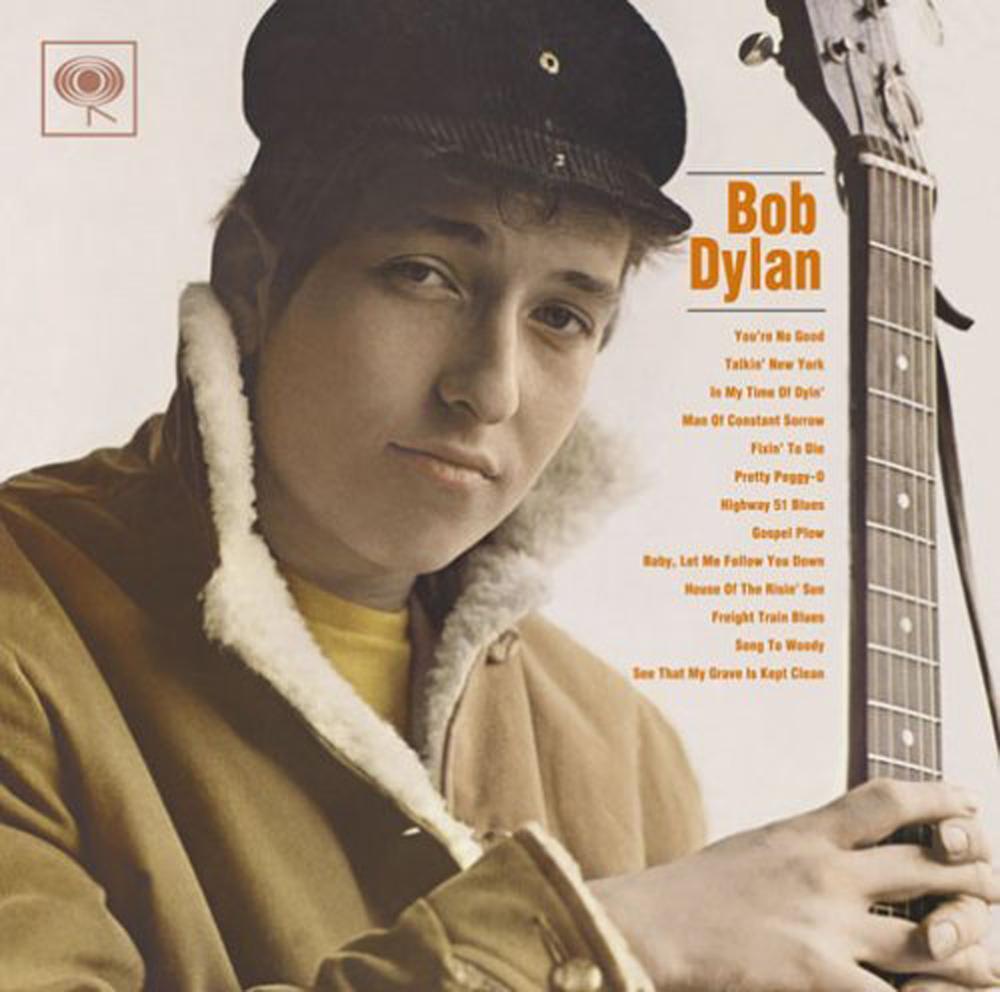

But the Bob Dylan of legend was just starting to emerge. It’s hard to picture him as the fresh-faced boy on the cover, barely out of his teenage years. It’s hard to picture him hiding his wild hair under the black corduroy snap-down cap that was his trademark at the time. It’s hard to picture anyone describing him as being like Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp, as the liner notes were sure to do (repeatedly). It’s hard to picture Bob Dylan before he wrote his own songs.

But in 1962 the lyrical master that was to develop was not yet present. In fact, Bob Dylan contains only two originals to go along with eleven traditionals. By the time Freewheelin’ came out just over a year later, that ratio would be flipped on its head. By his next album, Dylan wouldn’t be doing any covers at all, something that would continue for the rest of his career with few exceptions. Bob Dylan is the only time the artist really showcased himself as a folk musician, playing traditional songs. It therefore gives a glimpse at the influences that molded the legend to come much more clearly than any of his other works.

For instance, the songs are all sung in a raw style, perhaps described as backcountry or hillbilly or, as in the New York Times article quoted on the cover, with “all the ‘husk and bark’ left on his notes.” Traditional folk singers, before the age of radio began to distil their sound, had their own local conceptions of what made for good singing, many of which are harsh or unpleasant to the modern ear. Dylan seemed to revel in this style, picked up through old recordings of artists such as Woody Guthrie, who didn’t exactly have a classically trained voice himself. In many ways this is the Dylan voice we all know so well, but it was a throwback unwelcome in the early days of the 60’s folk revival, which was based on Weavers-style “citified” folk, rather than the old roots. That 50’s folk supergroup—despite their own deep traditional roots—had taken the originals and cleaned them up for public consumption. It wasn’t Leadbelly’s version of “Goodnight, Irene” that Frank Sinatra covered—that would have been too inaccessible for a popular audience—it was the Weavers version that had reached #1 on the charts just a few months earlier. Dylan himself describes the situation well on “Talkin’ New York Blues” when he describes being rejected by a coffee house owner who tells him “You sound like a hillbilly. We want folk music here.” What was revolutionary about Dylan’s style on this album was that he dared to be unpolished and challenged his mostly urban audience to like it anyway.

Another key is in the songs he chose to record. For the most part, they are works with deep meaning. They tell tales that highlight the human condition—life, love, and, often death—giving the first glimpses of the themes that would stretch throughout his career. That last subject runs throughout the album in an eerie string. Even Columbia Records had to ask why a 20-year old singer was so enthralled with songs about death. I believe there are three main explanations in retrospect: a) the ailing condition of the musical hero who inspired much of his thinking at the time b) his early rejection as a folk singer and the feeling that he was engaged in a battle which he might not win and c) the concern for society as a whole and its position on a precipice that was just beginning to become evident as tensions ramped up between the superpowers and which—though largely absent on this album—would soon become recurring subjects in his music. Whatever the reasons, it shows a forward thinking that would soon infect the entire folk music genre through the influence of Dylan’s protest songs and his later, more complex writings, and then move through the society as a whole.

The first moments of Dylan’s recorded career in many ways set the pace for what would follow. “You’re No Good” starts simple and moves into a blistering pace, with thunderous strumming and wind-sapping harmonica blowing. Dylan’s distinctive voice crackles under the strain of its exaggerated style and melodramatic lyrics. One wonders just what someone hearing that voice for the first time must have thought, absent the gigantic reputation that had yet to be attached to it. “Is this guy joking? Does he think he can sing? What is this? Wait a second. Huh. Actually, this is pretty good…”

The following track, “Talkin’ New York Blues,” was Dylan’s first original song ever recorded, but it’s written in an old traditional style: the talking blues. Favored by such predecessors as Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly and such followers as Phil Ochs and Townes Van Zandt, it is characterized by spoken (though cadenced) lyrics, rather than singing. The same style would be used on Freewheelin’ in the form of “Talkin’ World War III Blues” and pop up again throughout his career.

As in the other original on this album, the music is taken directly from a Woody Guthrie song (which, as with all of Guthrie’s music, was itself taken from a yet-older work). It is a comical piece that tells the story of Dylan’s first go ‘round in New York. As he tells it, after nearly freezing to death, he braved the subway and ended up in a Greenwich Village coffee house where he is told he sounds too much like a hillbilly to be a folk singer. After a few more tries:

Well, I got a harmonica job, begun to play,

Blowin’ my lungs out for a dollar a day.

I’d blow it inside out and upside down.

The man there said he loved my sound.

He was raving about it. He loved my sound.

Dollar a day, it’s worth.

After many such adventures, Dylan concludes:

Now a very great man once said,

That ‘Some people rob you with a fountain pen.’

It don’t take too long to find out

Just what he was talkin’ about.

In the end he decides to ramble back out West with the words:

So long, New York.

Howdy, East Orange.

Although telling Dylan’s own story, the song is full of Woody Guthrie’s language. For instance “a dollar a day” is the wage Woody claimed to make in his song “Hard Travelin’,” while “Some people rob you with a fountain pen,” comes from “Pretty Boy Floyd,” his tribute to the Oklahoma outlaw. The most interesting aspect of this song is the glimpse it gives into the life of an unknown artist in the city, especially one like Dylan who is trying to sail against the prevailing wind. As noted before, the folk music he was trying to play was more traditional than the refined sound that had gained popularity in the Village at the time, and it wasn’t until he was accepted by such citified singers as Peter, Paul & Mary that the doors began to open for him.

“In My Time of Dyin’” is a blues tune and starts off the death themes prevalent on this album. Dylan twangs the guitar perfectly as he sings in a steady monotone that rises in steps as he strides into the chorus or clips up suddenly under the strain of the emotion in more powerful moments. The liner notes point out that Dylan fretted his guitar with a lipstick case belonging to his girlfriend, artist Suze Rotolo (here noted as Susie), who is perhaps most famous as the girl pictured walking down Jones Street with him on the cover of his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. This gives the sound a particularly vibrant metal twang rarely heard at the time outside backcountry performances.

Many modern listeners know one of the most famous folk songs of all time, “Man of Constant Sorrow,” from the “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” soundtrack, where Union Station member Dan Tyminski played voice double for George Clooney. However, the song’s roots go back almost to time immemorial and the singers of Appalachia. It tells the story of a troubled rambler trying to make it any way he can. Oddly, where the traditional lines read “I bid farewell to old Kentucky, / Land where I was born and raised,” Dylan changes it to Colorado. Minnesota would have fit and would have been biographically accurate, but at least it’s not as poor a choice as Peter, Paul and Mary inexplicably moving the location to California. This version is relatively slow and justifiably sparse, with the guitar highlighted by harmonica notes between the verses.

A fast-paced, fast-strummed, hard-hitting piece, “Fixin’ to Die” doesn’t describe exactly why the narrator feels death is impending, but it does describe the situation with a certain flair and nonchalance—almost bravado. “I’m walkin’ kinda funny, Lord. / I believe I’m fixin’ to die,” Dylan bellows, defiant in his resolve as he concludes, “Well, I don’t mind dying, / but I hate to leave my children cryin’.” His voice is filled with emotional vibrato and his hands fly across the guitar strings, punching out almost every note.

“Pretty Peggy-O” starts off with a spoken statement, “I been around this whole country, but I never yet found Fennario.” This is in reference to the first lines of the song as he sings it, which are:

Well as we marched down, as we marched down,

Well, as we marched down to Fennario,

Well, the captain fell in love with a lady like a dove.

The name that she had was pretty Peggy-o.

The fact that the place does not appear on a map is easily explained: this song about the thwarted love between a soldier and a young maiden comes from Scotland, and over there the reference is to Fyvie-o, Fyvie being a town near Aberdeen. The first recorded version, amazingly enough, was made in 1951 by archivist Alan Lomax, sung by local farmer and balladeer John Strachan. Although the rendition here is far briefer than the Scottish version, Dylan nevertheless rewrote or added several of his own verses, and whether the change in location was made by Dylan or by another American through whom he collected the song, it has now become the standard version in the States.

As with many of the songs on this album, he seems to play it all in one breath, spitting out the lyrics, blowing the harmonica, and shouting “Woooo hooo” without pause between. When he sings the guitar is hushed, but between verses it thunders to life and his harmonica flairs up into a screaming series of notes so rapid he barely has time to articulate them. It is full of the vigor of youth and this remains perhaps the liveliest rendition of the old traditional ever recorded.

A song that the cover notes describe as “Diesel-tempoed” (I like that), “Highway 51” is played lightning quick. Although the highway is described as the road that “runs right by my baby’s door,” the song continues the morbidity theme with the lines:

If I should die before my time should come

And if I should die before my time should come

Won’t you bury my body out on Highway 51?

It ends with the declaration:

If I don’t get the gal I’m lovin’

Won’t go down Highway 51 no more.

The fast pace seems in keeping with the idea of a young man living life in the fast lane, knowing that it may lead to disaster. It reminds one that Dylan really was a rebel in his day, staking out a path in life that was by no means assured of success. The song stands as a statement that no matter what others said he would do what he thought he needed to, torpedoes be damned. Only fools and geniuses choose to swim through such waters, and only the geniuses have a fair shot at coming out alive. At this time it was far from clear which of these Dylan would prove to be.

Leading off the second side, “Gospel Plow” is another early American traditional that Dylan turns on its head. He thunders through the religious tune like he can’t wait to get to the Pearly Gates. Again, the guitar is toned down while he is singing but springs to life in between, with the harmonica blowing up a storm. The lyrics are appropriately filled with religious imagery:

Mary wore three links of chain,

Every link was Jesus’ name.

...

Mathew, Mark and Luke and John,

All them prophets are dead and gone.

He shouts out lines like these in what can only be described as a fervor. His voice breaks with emotion as he screams:

Oh, Lord, oh, Lord!

Keep your hand on that plow.

Hold on!

It’s obvious that if he’d wanted to he could have converted more lost souls than any tent revival preacher. He seems completely at home with the come-to-Jesus zeal. Even at a time when his Judaism was still in tact, he had no problem cranking out an incredibly spirited version of a Christian spiritual, and this is undoubtedly one of the most powerful renditions of this song.

Taking the tempo down a notch, “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down,” is a sweet and sincere love (or lust?) song. As Dylan describes at the beginning of the track, he learned the song from contemporary folk singer Eric Von Schmidt (referred to as “Rick”), whom Dylan met “in the green pastures of Harvard University,” where he was the leading light of the Cambridge folk revival in the early 60’s. With a bluesy harmonica at the fore, the short song (just a minute and a half once past the intro) contains aching proclamations of longing like:

Baby let me follow you down.

Baby let me follow you down.

Well I’d do anything in this God-almighty world

If you’d just let me follow you down.

It is nothing if not pithy, packing an amazing amount of emotion into just two verses.

One of the most oft’-sung ballads in American musical history, “House of the Risin’ Sun” is given one of its most impressive treatments here. On the liner notes, Dylan said he learned this version from Dave Van Ronk, but elsewhere he has stated that he first heard it via old recordings by blues singer Josh White, the same source drawn upon by the Animals when they recorded their famous version. Unlike the Animals and many modern adapters, however, Dylan had the balls to sing the song from the traditional perspective, the woman’s point of view. This gives it far more resonance than any of the later versions. (Besides, what john has ever had his life ruined by a whorehouse? …unless he got syphilis there.) This version is classically bluesy and sung with tremendous emotion, as Dylan is able to perfectly relate the turmoil of his subject’s life, despite the difference in gender.

With a harmonica that sounds like a chugging engine and a guitar like rolling wheels, “Freight Train Blues” came to Dylan through the recordings of Roy Acuff. At one point he holds the word “blues” out for fifteen seconds in a fair impression of a train whistle, his less-than-operatic voice evident as it always was. The song moves along at a pace befitting its subject. In its power if not its music it presages his later turn toward rock.

The reason Dylan originally came to New York was to go to New Jersey. That perhaps makes him unique in the entire history of the city, but Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital was one of several institutions in the Garden State where the otherwise-immortal Woody Guthrie spent his last years as life ebbed away and Huntington’s Disease ravaged his body. Dylan made many pilgrimages to see the ailing singer starting in early 1961. Although Guthrie was by then barely able to speak and had long lost the ability to play the guitar, he enjoyed listening to Dylan play his old songs.

The fact that Guthrie was Dylan’s strongest influence at the time can be seen throughout the album, but—as previously noted—especially in the two originals. In addition to being written essentially as an open letter to the man, the music for “Song to Woody” is taken directly from Guthrie’s song “1913 Massacre.”

The lyrics tell of Dylan’s travels through life to that point. He looks both to the past and the future, seeking out and listening to “paupers and peasants and princes and kings” trying to figure it all out.

Hey hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song

’Bout a funny old word that’s a’ comin’ along.

Seems sick and it’s hungry. It’s tired and it’s torn.

It looks like it’s dyin’ and it’s hardly been born.

These sentiments could just as easily come from Guthrie's pen, and the tribute doesn't end there:

Here’s to Cisco and Sonny and Leadbelly, too,

And to all the good people that travelled with you.

These lines reference friends and frequent Guthrie collaborators Cisco Houston, Sonny Terry and Huddie Ledbetter and make the connection between musicians and dreamers throughout the ages. At the end, Dylan sings:

I’m leaving tomorrow, but I could leave today.

Somewhere down the road someday,

The very last thing that I’d want to do

Is to say I been hittin’ some hard travellin’ too.

This last bit is a another reference to one of Guthrie’s most famous songs, and is perhaps an optimistic note that Dylan still believes his generation can make things better than they were for those who lived through the Depression-era travails of Guthrie’s day.

Although certainly not among Dylan’s greatest or most poetic of compositions, it does show glimpses of what was to come. This song is essential for understanding the nascent genius that lay within the young artist and for comprehending the framework of thinking that ran through his protest-song era and that would allow him to break out just a year later with such brilliant works as “Masters of War,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” and “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Those who haven’t heard it and don’t understand Dylan’s personal connection with Dustbowl balladeers such as Guthrie are missing a key link in his psyche.

The final selection is a fast-paced rendition of a blues number by Blind Lemon Jefferson and continues the death themes emblematic of this album. Again told from the perspective of someone expecting death, it asks the listener for just one favor, to “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.” The passion in Dylan’s voice is striking, and only highlighted by the heavy hand with which he strikes the steel strings. “Now my heart’s stopped beating and my hands turned cold,” he sings. “Now I believe what the Bible told!” His voice trembles as these lines pour forth, emblematic of the trepidation behind the words of assurance.

The fact that this album was influential at the time is indisputable, and in some ways it was revelatory in the burgeoning folk revival movement. Several of the versions first recorded here have become standard. But it has become nearly forgotten today under the weight of Dylan’s later works, and it shouldn’t be. Standing alone as a folk music collection, it is absolutely fabulous. The renditions included are powerful and heartfelt and they point towards a much truer north than was common on most other folk revival albums.

But just as important (or perhaps even more) is what the work says about Bob Dylan himself. The number of people out there who think that they know Dylan but don’t know this album is frightening. It’s impossible to really know his work without understanding how it started. You can’t fathom the emotions that led to his protest era unless you can see the building blocks that preceded it. You can’t understand the electric era unless you can understand his acoustic influences. You can’t understand his preacher era unless you’ve first heard him sing a traditional gospel song. None of the pieces fit together without the keystone. With all irony intended, without Bob Dylan you simply cannot understand Bob Dylan.

| mp3 | cd |

|---|---|